Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

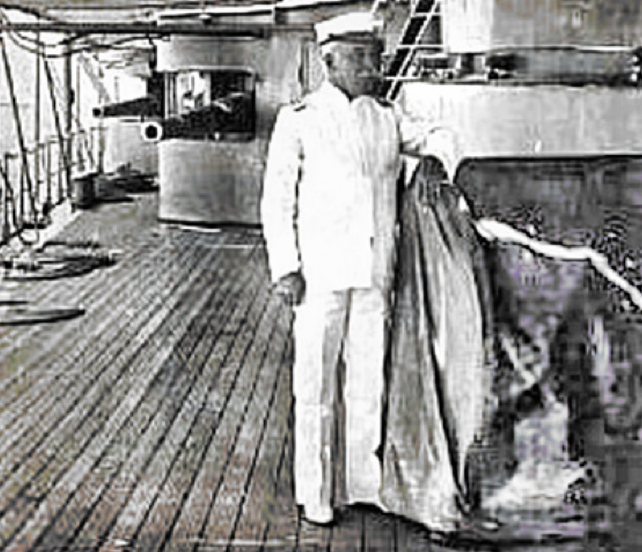

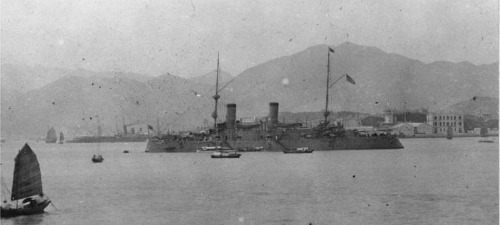

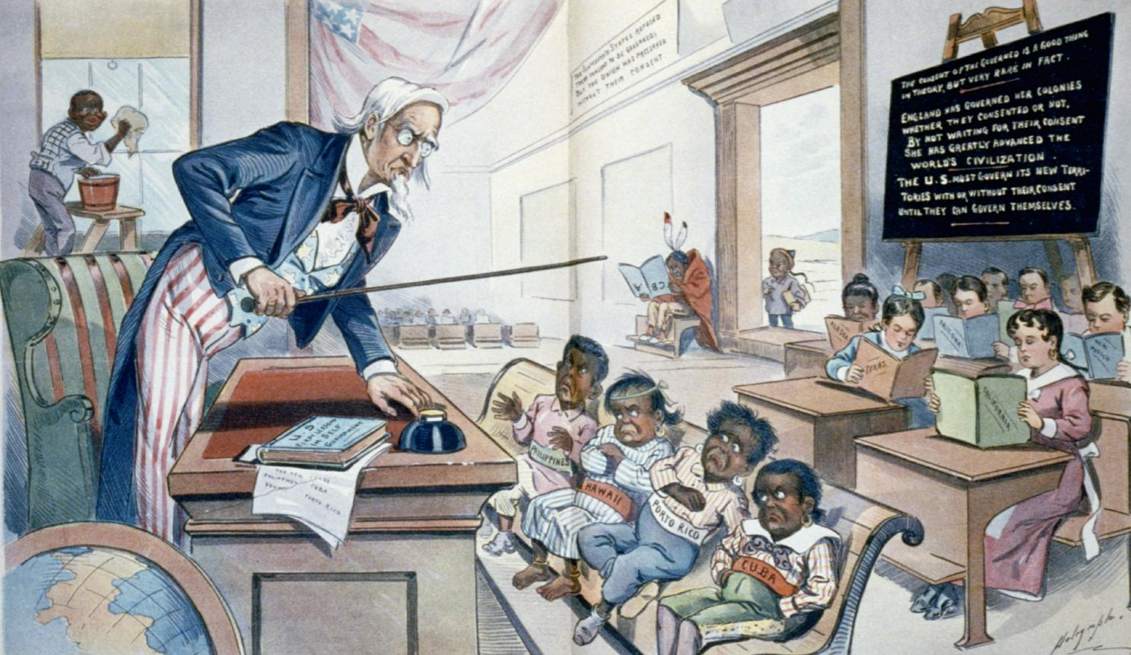

America’s official involvement in the Philippines began in 1898 when Commoodore (soon to be Admiral) Dewey sailed the Asiatic squadron from Hong Kong and defeated the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. With the help of Filipino revolutionaries who fully expected to be granted independence, , the Americans succeeded in ousting Spain — but after doing that, rather than give the country its freedom, America took the Philippines as a colony. The Philippine-American War ensued, followed by fifty years of American colonial rule of the Philippines.

For me, it is difficult to find any American “heroes” emerging from this. But there is one: James H. Blount.

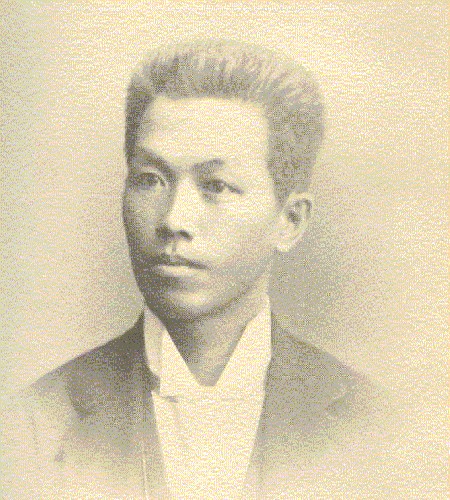

Blout had a unique perspective. He fought against Spain in Cuba in 1898 , then was transferred to the Philppines where he saw combat as an Army officer from 1899-1901. He was one of five American Army officers who were asked by Governor Taft to resign their commissions in order that they may accept civil position in America’s colonial administration in the Philippines. He was appointed a judge, eventually trying cases through Mindanao and the Visayas. He became intimately acquainted with the Philippines, and came to believe that the Filipinos were deprived unjustly of the liberty that had already won. He returned to the US in 1905 and became a leading voice in Anti-Imperialist Circles, giving speeches and lectures and writing articles all of which were focused on calling attention to the injustice of America’s policy toward the Philippines, culminating in 1913 with the publication of “The American Occupation of the Philippines 1898-1912”.

His introduction to his book says it all–and in a way, articulates not only what he set out to do with his book:

This book is an attempt, by one whose intimate acquaintance with two remotely separated peoples will be denied in no quarter, to interpret each to the other. . . .The task here undertaken is to make audible to a great free nation the voice of a weaker subject people who passionatelyy and rightly long also to be free, but whose longings have been systematically denied. . . . sometimes ignorantly, sometimes viciously, and always cruelly, on the wholly erroneous idea that where the end is benevelot, it justifies the means, regardless of the means necessary to the end.

“Occupation” begins at what is arguably the beginning of America’s adventure in the Philippines — with American Ambassador Spencer Pratt in Singapore in April 1898 at the time of the outbreak of war between America and Spain. Meticulously researched and vividly re-created, Blount recounts how Pratt approached Philippine leader Emilio Aguinaldo, then exiled in Singapore, and engineered for Aguinaldo to go to Hong Kong and present himself as an ally to Admiral James Dewey, who was then preparing to sail to Manila to confront the Spanish fleet. Blount is unequivocal in stating that Pratt absolutely did promise Philppine independence to Aguinaldo, doing so without authority and with the result that soon thereafter, Pratt was separated from the consular service and forced to retire.

“Occupation” begins at what is arguably the beginning of America’s adventure in the Philippines — with American Ambassador Spencer Pratt in Singapore in April 1898 at the time of the outbreak of war between America and Spain. Meticulously researched and vividly re-created, Blount recounts how Pratt approached Philippine leader Emilio Aguinaldo, then exiled in Singapore, and engineered for Aguinaldo to go to Hong Kong and present himself as an ally to Admiral James Dewey, who was then preparing to sail to Manila to confront the Spanish fleet. Blount is unequivocal in stating that Pratt absolutely did promise Philppine independence to Aguinaldo, doing so without authority and with the result that soon thereafter, Pratt was separated from the consular service and forced to retire.

Blount then traces Aguinaldo’s dealings with three crucial Americans: Dewey, and Generals Andersen, Merrit, and Otis. Out of these four relationships comes the most reasonable and balanced account I have ever read of just how it happened that America granted independence to Cuba but not the Philippines — yet gave Filipinos the clear impression that independence would indeed be forthcoming. My Filipino friends who think much about such things tend to simply believe that Dewey “lied through his teeth” to Aguinaldo, to gain the latter’s cooperation. Blount’s beat by beat explanation, coming from someone who is sympathetic to Filipino aspirations but also a good researcher and one who is aware of “the way things are” in the US Government — manages a compelling explanation for just how Dewey came to mislead Aguinaldo which has the ring of truth and reality.

One of the first points which Blount reminds us of is that Aguinaldo never met with Dewey in Hong Kong — he arrived the say after Dewey sailed, and came across from Hong Kong to the Philippines on the Mccullough, arranged by Pratt’s counterpart in Hong Kong, Consul Wildman, who like Pratt clearly led Aguinaldo to believe that Philppine independence was in the offing , as evidenced in a letter he wrote to Dewey in which he wrote:

Do not forget that the United States undertook this war for the sole purpose of relieving Cubans from the cruelties under which they were suffering, and not for the love of conquest of the hope of gain. They are actuated by precisely the same feelings for Filipinos.

General Andersen, one of the other interlocutors who would be implicated in misleading Aguinaldo, was quoted in 1900 in the Chicago Record as saying:

Every American citizen who came in contact with the Filipinos at the outset of the Spanish-American War, or any time within a few months after hostilities began, probably told those that he talked with that we intended to free them from Spanish oppression. The general expression was, “We intend to whip the Spaniards and set you free.”

One of the interesting aspects of Blount’s account is the degree to which it shed’s light on the state of Dewey’s likely knowledge, or lack of knowledge, about America’s ultimate policy toward the Philippines during the period between May 1, 1898, when he defeated the Spanish Armada in Manila Bay, and June 30th, when American ground forces finally arrived, bringing with them not only their military capacity but also news of the evolving view of the Philippines as seen by an America who had wandered into the Spanish American conflict without much thought about the Philippines–most of the focus being on Cuba.

As recently as December 1897 President McKinley had gone on record stating that war with Spain would never be fought with “forcible annexation” in mind: “That by our code of morality would be criminal.” And indeed the Teller Amendment, necessary to gain the vot in Congress necessary to authorize the war, explicitly stated that American could not take Cuba as a colony, but would instead grant independence. The Americans first present n the Philippines seem to have assumed that the Teller Amendment and statements of the “criminality” of forced annexation would apply — and thus freedom would be granted to the Philippines, same as Cuba.

Blount doesn’t give Dewey a “pass” on having contributed to the deception – rather he just provides the kind of intelligent context necessary to make the whole sorry episode understandable to anyone who cares to try and imagine how it actually went down.

Chapter after chapter, with great verve and not a little caustic wit, Blount recounts each of the beats of America’s historic involvement in the Philippines. He buttresses his own observations with extended quotations from the subsequent congressional testimony of Dewey and others, and puts a microsope onto the performance of a series of American military leaders, and then governors general, in the Philippines.

In the end, Blount throws his backing to the Mcall Resolution, which was then a proposal popular among anti-imperialists for an early grant of independence to the Philippines, coupled with guarantees that the Philippines would be “neutral” in a manner analagous to Switzerland (this to counter the argument that if America left, another great Power would move in and take over).

The McCall Resolution read:

JOINT RESOLUTION

declaring the purpose of the United States to recognize the independence of the Filipino people as soon as a stable government can be established, and requesting the President to open negotiations for the neutralization of the PHilippine Islands.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America: in Congress assembled:

That in accordance with the prinicples upon which this overnment is founded and which were again asseterd by it at the outbreak of the war with Spain, the United States delares that hte Filipino people of right ought to be free and independent.and announces its purpose to recognize their independene as soon as a stable government, republican in form, can be established by them and thereupon to transfer to such goeverment all its rigths in the Philippine Island s upon terms which shall be reasonable and just, and to leave soverignty and ctonrol of their country to the Fililpino people.

Resolved, That the Preisdent of the United States be, and he hereby is, requested to open negotiations with such foreign Powers as in his opinon would be parties to the compact for the neutralization fo the PHilippine Islands by international agreement.

That was 1913. In the end, it was 1946 before the Philippines would be released from the ‘claws of the eagle’ — but it is worth remembering that there were good Americans like Blount who “got it” long before the American government finally “let go” ….. they are worth remembering, as Blount is, for taking a stand that was less than popular, but which was right and consistent with the veryp rinciples on which America had been founded, and which its leaders seemed to forget.

It’s a great book and it’s free.

2 Responses to Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Year of the Spy Book Trailer

Above is the Year of the Spy Book Trailer — for my upcoming non-fiction book about espionage upheavals on the streets of Moscow in 1985.

Below is a “trailer” showcasing the writing and video services I provide to clients.

Michael Sellers — Writing and Video Services

My eBook — Just released Dec 5, 2012

EBook You don't need a Kindle or iPad -- Download Adobe Digital Editions for Free, then read the .mobi (Kindle Format) or .epub (Nook, iPad Format) digital book on your computer. Or order the PDF which is formatted exactly like the print book.Recent Posts

- Arsha Sellers — Today I’m One Big Step Closer to Becoming a Real Forever Dad

- Meet Abby Sellers and Arshavin Sellers — My Wife, My Son, My Inspiration Every Day

- What the Mueller Report Actually Says

- Remembering James Blount, an American Who “Got” the Philippines in 1901

- America the Beautiful? You Mean America the Pitiful. I Am Ashamed

zluh9e

Very informative..but disturbing revelations!!